Category Archives: Fall 2022

Passing Clouds

Tara Harbo

St. Catherine University, North Carolina, USA

A cold fog dances over the black water, tickling at the branches and teasing the shore. In between the pitch-wash of the summer clouds, the moon glances down, its gaze carving through the mist, casting uneven shadows on the open river. Moths and water-flies follow its lead, braving the rapids just to bask in a momentary glare. Then the next cloud passes, the stream hazes over again, and the insects fall silent, waiting for the next glow to return to lead their next dance.

Four canoes lay beached in a small cove, just out of reach of the dark eddy. In the shade of the gnarled forest, their hard-plastic hulls look like cockroaches, fit with a mess of abandoned paddles as uneven legs. Each shell is neatly stamped with a simple tent logo, chipped and peeling, with the words “property of Camp Vermillion” underneath it. That same stamp adorns a handful of tents up the shore, gathered around the embers of an evening campfire.

A girl unzips one of the tent flaps and pokes her head out. With one hand, she eases the zipper open another six inches, and with the other she pulls herself out onto the tarp. The camp has an earthy smell to it, laced with a bitter edge – the musk of a burnt prairie mixed with the more mild air of an algae bloom. She blinks it off and hauls her duffel bag out. Then, with as much care as she took on her way out, she closes the flap, leaving the soft snores of her tent-mates behind.

The trail down towards the water is a scramble. Pebbles bounce and scratch over exposed roots as the girl slips down to the shore. She leans on a canoe long enough to ease her windbreaker over her pajama shirt. The water bubbles a greeting. She dips down and splashes her face, rinsing the last of the sleep from her eyes.

She never meant to be there. At that camp. On that canoe trip. Sleeping out in the dirt – out with a troupe of boys. She had fully intended to spend the summer at her friend’s place, playing Mario Kart and dodging her parents. Instead she ended up staring out at passing fields on her way to a washed up camp, where her mother became lifeguard certified and her father “had a religious experience”. At least she still didn’t have to see either of them after they left her at the dinghy remains of the base camp.

“Maybe this trip will help you clear your head,” they said. “It’ll help you come to your senses.”

The girl grips the edge of the canoe on the end of the stack. It scrapes down across the rocks and towards the shore, sending a cloud of dust and bugs scattering towards the water. The thud echoes across the river, and she grits her teeth. None of the tents stir, so she pushes the boat closer towards the tide.

Neither the canoeing nor the camp were all that bad. Sure, the days were long, but there’s something peaceful about the pull of the current and the slow crawl of the forest. The problem was just the boys. They were rough, and they were loud. More than anything, they knew just what to say to hurt a person, even if they didn’t know exactly who was going to take it personally.

The water catches the bow of the canoe, lifting it and offering to pull it out the rest of the way. The girl hooks it with her leg and throws her bag in.

“Where are you going?”

The girl whips around, stumbles back over the gunwale, before steadying out. There’s a boy behind her (Liam, at least that’s what she thinks his name is). He blinks a couple of times as he shuffles closer to her. A flashlight glares down at her from one hand, obscuring the expression on his face.

“Turn that off!” She says. The canoe bumps back against her leg. She reaches to steady it, but the river pulls back, urging its bow towards the main current. Liam lunges after it, splashing into the shallows. Murk laps at his ankles, then at his knees. He catches hold of the rim, and yanks it back towards the girl.

“[DEADNAME], what the fuck were you thinking?” Liam’s fully awake now.

“Come on, keep it down,” the girl holds a finger to her lips.

“Okay, okay.”

Maybe stealing a canoe in the middle of the night wasn’t the best plan. Actually getting it into the water was a question from the start, but it wasn’t so bad when compared to the thought of trying to steer a whole boat alone. Then again, it meant no more camp and no more boys.

Liam hefts the pack out of the bow and back onto the rocks. He wrings out the legs of his sweatpants, intermittently grunting and shooting daggers at the girl. (He’s such a fucking counselor’s pet.)

“What’s your deal? Just go back to your tent.” She says.

“What’s my deal? [DEADNAME], You’re the one trying to steal a fucking boat!” Liam eases himself to the ground as he tries to wrestle his drenched socks off. There’s one wet slap and then another.

“Well?”

“Why are you even up?” The girl stoops down next to him just long enough to grab her bag. He grabs her wrist.

“That’s really not an answer.”

She shrugs.

Liam sighs deeper than he had before, “I couldn’t sleep. My sleeping bag has a hole in the foot and I got cold.” He looks out towards the river. Lightning bugs glow on the water, highlighting the subtle swirl of the eddy.

“Sure.”

“What, it’s true! That’s it [DEADNAME]. At least I’m not out here to steal a goddamn boat,” he flicks a pebble into the shallows. The silhouettes of minnows flit off for darker waters.

“You need to stop calling me that.”

“Oh.” He blinks, “what did you want me to call you?”

The name was what had thrown off her parents the most. When she came out to them, she asked their input – what would they have named her had she been born a girl? Her mother left the room and her father yelled. “You’re denying reality,” he tried, “how can you throw away what we gave you?”

“Marissa. Mara? I don’t know. Just not that,” Liam watches the girl stand back up and toss her pack back into the boat. She reaches over him for a paddle and a life jacket. With one more glare, she vaults over the gunwale and into the seat at the stern.

“For fucks sake,” Liam pitches after her, half leaping, half tripping into the back of the boat. The canoe rocks, and they both hold their breath as they glide out of the eddy and into the current.

The moon glows brighter from outside of the canopy, as it slices the midnight mist to ribbons. Out here the air is clear, free of the smell of charcoal and ash.

“Seriously?” The girl lifts her paddle clear of the water, letting the tide steer the boat downstream, “just let me go.”

“It’s a little late for that!”

She scoffs, spitting into the water, “nobody would have noticed if you hadn’t come with.”

In all fairness, Liam was the loudest of the campers. He was a leader, a wannabe counselor, and most apparently of all, a complete suck up – the cheeriest singer of the thirtieth line of “ninety-nine bottles of beer on the wall” and that kid that always advocated to put the rain fly up, even on the driest of nights.

“Yeah, I think they’d notice a missing canoe in the morning.”

“So you’re acknowledging that they wouldn’t miss me?”

Liam rolls his eyes more enthusiastically than he spouts shitty lyrics, “that isn’t what I said!”

The landscape blurs past as the canoe begins to pick up speed.

“I get why you want to run away, I really do,” the boy says. He grits his teeth against the cold of the fog as they round a bend.

“But you actually want to be here.”

“I didn’t always. Last year I was in a girls cabin, which… ummm, wasn’t really…it for me,” He says, gesturing to his outfit – a bright Star Wars t-shirt and a pair of sweatpants. The girl rolls her eyes.

He runs a hand along the surface of the water. The moon ripples off the wake, sending a glittering mist up and through the breeze, “I didn’t let my parents win. Instead of trying to let the camp ‘fix me,’ I treated it as a moment to prove them wrong. To be myself and still make friends anyway, even though I didn’t completely fit in.”

The girl shakes her head, “I can’t go back to my parents.”

“I didn’t say that you should, but how far did you think you’d get in a stolen canoe?”

“Far enough.”

“Without any food?”

A log floats past the canoe, its surface covered in moss. It bobs beneath the surface and sounds against the hull, a weighty thunk, followed by a long, sharp scrape. The girl’s eyes go wide as it passes.

“You-,” she pauses, “-ugh, fine. But no promises that I won’t steal food and try again tomorrow night.”

“Thank you.”

She dips the paddle into the water and scoops backwards, swinging the boat sideways. It’s an upstream battle back towards the camp. They push in sync, carving back into the cove.

“And for the record, I think that Marissa is a beautiful name.”

The girl’s cheeks flush, “thanks,” she climbs into the shallows, dragging the bow of the canoe back onto the rocks. “That, umm, that means a lot.”

Liam loops her bag onto his back, depositing the paddles back onto the shore. They flip the canoe and line its faded stamp up with the others.

“Could you, uhh, keep this whole thing on the down low?”

“Keep what on the down low?” Liam’s lips light up with a mischievous grin. The girl punches him on the arm.

“Thank you, and g’night Liam.”

“Night Mar’s.”

They walk the trail together, back up the scramble and towards their own, separate tents. The moon blinks through the leaves, and then disappears back behind a cloud, shrouding the river and the forest alike in that cold, dark fog.

Cuts

Diadou Sall

St. Catherine University, North Carolina, USA

The smallest cuts are the most painful.

You don’t know where they are,

When you get them,

Or who you get them from,

But you know they’re there.

Sending sharp tensions,

Down its desired path,

Both skin-deep and shallow.

Some a clean shot straight through the heart,

Others a mere pinch.

It’s there.

Small, yet discreet.

Sometimes you feel them,

And they hurt,

But others,

You forget they’re there.

Like the slums of their sorrow missed you

On its way to another,

Cursing them with its touch.

But it chose you.

It marked you,

Again and again,

Tricking you into thinking it’s gone,

But catches you at your most vulnerable.

It’s there.

Watching and waiting,

For the most perfect moment to strike,

And even risks it sometimes,

Losing its patience to take you down,

Wanting you now more than ever.

Here more than there.

It’s there.

It knows everywhere you are,

And everywhere you’ll be.

2007

Mirror Mirror on the Wall

Ritika Das

Indraprastha College for Women, New Delhi, India

Mirror Mirror on the wall, it is a cliché question to ask but who am I?

What do I reflect to the world, what do I reflect to my surroundings?

What do I reflect on myself?

I try to look deep into the tinted glass frame hanging in front of me, trying to understand my true identity, my true reflection.

But all I can see is a shadow of mine which is constantly made and broken by society.

I often try to see my reflection in the physical wounds that are a result of that weighed wedding band in my finger,

I portray the role of a good wife but all I can see is a timid and powerless woman.

When the same children who I nurtured yell their offensive frustrations at me, I try to gulp everything by thinking that I am just a mother who has over pampered her children.

But deep down I know, I am a reflection of a mother who is too submissive to even raise her own voice.

While trying to be a hands-on mother to my children, I have forgotten about that ailing old woman who lives miles away, my mother.

Mirror Mirror on the wall, that fact that I reflect an image of a failed daughter is not oblivion to me.

A pile of worn out scribbled papers are still lying somewhere amidst the dusty newspapers. The writings on the paper were meant to find a publisher but all it can do now is look through the adjacent window at the many shades of colour that the sky has in its palette.

Mirror Mirror on the wall, why can’t I see my younger self who wanted to become a storyteller, had cliché dreams of conquering the world and swaying people with her writings?

Why all I can see is a woman who looks tired by playing the same set of roles each and every day?

The mirror tells me to not be so harsh on myself because standing in front of the mirror, I am not the only one asking these questions. There are so many other people who, just like me, are stuck in the loop of life.

There are so many people like me who have a capability to think but not an ability to speak.

Mirror Mirror on the wall, the world may never know about my existence, about my identity but it would always be you who has witnessed my reflection from an attractive luminous light to a somber one.

Mirror Mirror on the wall, I may not stay that long to tell my story, but I know you will be there to give a reflection of my story, unless you are broken, just like me.

Aanti of the Puddle

Chanelle A. Bergeron

Meredith College, Raleigh, North Carolina, USA

His name was hard to pronounce, so most people avoided it. A soft string of vowels made

it begin like a sigh in the mouths of those who preferred the sharp cluck of a consonant at the

front. His name hung like fresh water in the mouths of people who preferred truncated sounds.

Our sounds landed like the thud of an axe against wood, like the bark of a dog left out in the

yard.

He wore blues and reds, mostly, and he wore boots. Leather ones cuffed at the top like

the collar of a shirt, the light tan hide a color close to custard. These things made him stand out

amongst the rest of us, these blues and reds, this custard against our differing shades of green:

moss, forest, pea.

I was younger then, I was thinner, I was sanguine. My hair reached well beyond my

shoulder blades, and I could swim for miles in salty or fresh water. In water my hair trailing out

behind me in long unconcerned strands. I was one of the only people in the whole town who could swim at all, or even cross a puddle without fear or hesitation.

In the morning, the sky is reflected on the water but in the afternoon, if I looked closely,

it was my face and the sky, warbling on the surface of the water. On those days, I would step in.

Step into my reflection, step into the sky, wade into the water. Under its surface I would practice

pronouncing the water’s dense, droning sounds. On these days, my mouth filled with water, with

lake, and so I learned that water would take the shape of anything it was held by.

It was said that I was born in water. I never met my mother. I was always told it was

January when she had swum out past the pier where the seals bob and buoy and disappear. I

could never know for sure. But it was said that I was born in the caul. That I arrived in the world

with a wet veil still covering me completely, that I was still breathing water when most babies

would have taken their first, sharp breath of air.

My mother was said to have swum out on the coldest day of the year, ice like shattered

glass floated in the water. The sun bright and the moon still in the sky and the pier covered in

snow, in frost. The townspeople took me in, as they did all orphans back then, and never spoke

directly about my mother. Only in fragments, only in threads. Only over the phone to one

another as a casserole baked in the oven, and there was the need to remark that I was beginning to look more like her around the mouth, the long stoic neck, and in the inner webbing of my small hands.

I was almost always in water, but rarely in baths or bed or the pew at church on

Wednesday evenings when everyone liked most to go. Instead, I would go to the lake with my

books and read them underwater, my eyes open and taking in the words which moved like little

fish across the page. It was easier to turn the pages underwater than above, one simply needed to go slowly and densely like in a dream. When I couldn’t swim, I would go to the river and put the pebbles in my mouth, sucking them for their flavor of mineral and warm rain, returning them

back to the water with great care when I was through.

When he arrived in town, I was younger and thinner and used to the sound of water. The

first time I saw him, he was standing in a puddle in the middle of town, and he seemed as if to

ripple. The people in our small town were shocked, of course, they mumbled and clucked and

pointed. They were fearful. Their green offended by his blue and red; their consonant shaped

mouths unsure, trembled.

When he arrived in town, he did not stay long. Long enough to stand in a puddle, long

enough to ripple. Long enough for me to walk right up to him and ask his name as the town

gawked behind us. Long enough for me to learn his name and to see his swimmer’s eyes

reflected in mine.

Dress By Gram. Curls By Mom.

Nikkole DeMars

St. Catherine University, Minnesota, USA

Throughout the course of my life, I never imagined that I would be the type of person to think that I was on a personal journey or transformation. You know, one of those corny opportunities for growth, change and self-acceptance that you see in posts on social media, or in the latest self-help book. It all seemed too superficial and cliché for me, and I certainly never considered my life to be some personal evolution; but unbeknownst to me, I was indeed on a quest for something that kept nudging at me with occasional whispers starting in my angsty teenage years. There was indeed something I needed to resolve within myself.

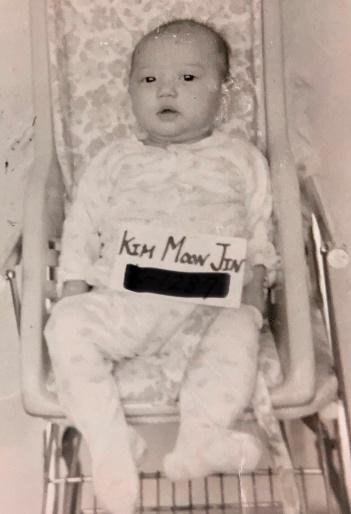

The story that I was told was that I was left on the front steps of an orphanage in Seoul, Korea by a woman who simply could not care for me. There were no additional details that followed that single phrase by my adoptive parents, but I never questioned whether that actually happened or not. Mostly because I was grateful for them choosing me, and I never wanted them to feel like they were not enough. I never wanted to be that “child of adoption” that wanted to look for their biological parents, or visit their birth place, but when I look back now, I guess I was always looking for clues that would lead me to understand who I really am.

Nature vs. Nurture

I was fortunate to grow up with a dad that was constantly creating a forum for fostering curiosity with my brother and I. Early on in my childhood I can recall him facilitating an environment for me to ask anything, and there was never a limit on how many questions I might ask. One of the repeated philosophical conversations that we would embark on in my teen years and into my twenties, was around the concept of nature versus nurture, and what has a more powerful impact on an individual.

Each time we engaged in this conversation, I always came up short on the nature side of things, and we would end up talking more about my brother, who is my parents biological child. I could definitely see the impacts of nature when we talked about it in terms of him and my parents. Honestly, I loved this debate because it allowed me to really examine the qualities within myself that were like my mother and father, and that gave me personal permission to feel deeply included in my family experience.

I have ingrained in me this incredible sense of appreciation and zest for life, I am a loud talker, a loud laugher, but I am also most comfortable in the content quiet and processing of my own thoughts and emotions. In my family, I am the “go to” person, the connector, and most times the life of the party. I have a high sense of value for fun, and a great appreciation for loved ones, friends and family. My dad also possesses all of these same qualities, and these shared qualities have given me comfort throughout my formative years and beyond. I really like being like him.

The Poop Diaries

There were many times during my childhood that I found myself quietly looking for clues as to what my short-lived life was like in Seoul (8 months to be exact). At the time. I really didn’t understand why that was important, but I wanted clues; hints beyond the one phrase of “I was left on the front steps of an orphanage in Seoul, Korea by a woman who simply could not care for me.”

Recently, my dad was cleaning out some old papers that he had in storage and mailed me a package that contained some things that he thought I might be interested in. To my surprise and quiet delight there was a small book in the package that was weathered and worn, and it looked to be some kind of small, thin journal from the orphanage in Korea. I wasn’t exactly sure what information would be contained in this small booklet, but I felt as though it must have something tangible for me to understand more about my experience there. As I surgically turned each page, thinking the next would bring out some juicy indications about my infant life, I quickly realized this was a daily journal that documented my eating habits and my bowel movements. That was not a leading indicator of anything juicy, other than proof that I was regular!

Although this was not the artifact that I was hoping for, it has proven to be a little something to hold onto. It was a sign that I was cared for, and someone was thoughtful enough to pass it along to my parents as a record of my health. It still feels like a treasure today, and I am grateful that my dad saved it all of these years.

N/A

Going to the doctor’s office and being asked to complete the standard medical history questionnaire has always been a complicated experience for me. When you don’t have any details of your medical history, these questionnaires are both easy and complex. The easy part is when you just write a giant “N/A – Adopted” over the whole page. The complex part is related to the emotions that bubble to the surface when the doctor enters the room, reviews your chart and responds to your response. I have had a variety of different comments from doctors. Everything from complete silence upon review of my “completed” form, to “I’m sorry”, to “Are you sure you don’t know anything about your history?”

I have never pitied myself, and was not raised to feel sorry for myself as a child of adoption so the one response that has always stood out to me is when someone responds to your sharing of adoption with “I’m sorry.” My family never treated me like an underdog or a less fortunate child so it was (and still is) shocking to me when someone looks at me through that lens.

Do you Want to See My Sister?

Another important tale that has been shared with me, starting when I was very young, is about the anticipation that my brother had regarding my arrival. He is three years older than me, and the story goes that once he heard that he was going to have a baby sister and that I was going to fly on a big airplane from far away with many other babies, he started asking anyone that he would encounter, “Do you want to see my sister?” Along with those words, he would reach into his front pockets and hold an invisible version of me cupped in his hands.

My brother and I are polar opposites at the surface in every regard. I am talkative and outspoken; he is quiet and thoughtful. I tend to be attention seeking, and he is introverted. I have a big personality, and he is reserved and more measured. I could list many dichotomies between the two of us, but the one main commonality that we do share is unconditional love and deep respect for each other. I have always felt that the relationship with my brother was built out of pure love, long before we ever met. He carried that invisible version of me around in his pocket knowing that we were going to share something unexplainable and uniquely special between us.

We shared all of the ups and downs that siblings share, and I could go on and on with funny and impactful stories about our relationship. Like the time I shoved an ice cream cone in his face just to get a reaction, or when he kicked out my front tooth with his moon boot, or when he offered me a couch to sleep on, and the encouragement to start my life anew after my divorce. I have always felt like my brother has treated me like a special treasure, even before we met.

Love and Kisses from Gram

She was the precise definition of glamour. Her clothes were classic, her home was stunning, her makeup and hair were perfection. In my eyes as a child, and still to this day, she was a mix between Marilyn Monroe, Zsa Zsa Gabor, and Martha Stewart. All beverages were served on a serving tray with tasteful accoutrements, and her vanity was chock full of the most beautiful lipsticks and eyeshadows, and glittering beautiful things. She even smelled glamorous.

When it came to the most important day of my childhood, my naturalization ceremony to officially become a U.S. Citizen, it was an obvious choice, that Gram would make me a special dress for my big day. If it is possible to “steal the show” at a naturalization ceremony, I certainly did that day. I paraded down the aisle in my dress by Gram, and my perfectly coiffed curls by mom, gripping and waving my personal sized American flag and blowing kisses to the onlookers and other new citizens.

I have come to realize that I feel like this little girl every single day of my life and that quest for understanding who I really am comes down to the people that have loved me, prioritized me and cared for me. In all of my efforts to seek my true self, I have come to recognize that you build your true self through everyday life, relationships, experiences, loss and traumas. The one through line in my life is the importance of human connection with those you love, and the acceptance that I am built by these people and experiences that have guided me along the way. Dress by Gram, curls by mom, always.

Play

Aswathy B. Surendran

Lady Shri Ram College for Women, New Delhi, India

My life had turned into a play,

the day we met.

I was a performer,

Surreptitiously breaking loose from reality.

With reckless words and polished dialogues,

But the audience didn’t matter at all.

Wretched like a prisoner,

Wrecked like a ship,

Shapeless like water.

I yearned for something distant,

To make it somehow,

Though withering, awaiting a fall.

Tempted by the rush

But only stillness surrounds,

So I slow-dance with time,

Bracing for a storm that won’t show up.

Silence abounds,

with eerie meanings.

Is it a caress of possibility?

A ride to the unknown?

A preparation for the storm?

An aftermath of ravages of desolation?

Or a collection of drab moments?

Is it a wait or an end to behold?

They say love can’t be earned.

Yet we starve, search and suffer.

Shattering into pieces to relearn that

Most don’t get love for free.

My words aren’t enough to fill this space,

Don’t want to know if there’s an end

Now, only memories allow moments to lend.

And that time has stalled with a hope to resume,

While I’m here, waiting on an empty stage.

you and me

Theo von Weiss

St. Catherine University, Minnesota, USA

Mother

Norah L. Tochhawng

Indraprastha College for Women, New Delhi, India

I am my mother.

I have her hands and my mouth settles into a quiet frown as the day grows longer.

When I’m tired and my legs ache from the weight of the children I bore,

I sit at the dining table and make myself tea - sweet, creamy and piping hot.

The mirror tells me a story I wish weren’t mine.

My skin, loose and coloured with weird lines and scars, has sagged from the burden of being a mother.

The image of youth is still a plague in my head.

And all the dreams I had to keep aside,

All the loving and the laughing that had awaited my arrival,

My whole life kept behind me so that I may wed.

The responsibilities I keep, the expectations I desire to meet,

Etched on my flesh like when my daughters drew on the plain white walls of our tiny apartment.

Some days, I find myself all alone in bed – cold and confused.

The tolls of my marriage gnaw at us and drive us apart.

I wonder then if I ever knew love at all.

When I have lived all my life, is this all that there is to it?

I cannot accept that the love I have for my daughters might be the only kind of love I’ll ever know.

I have my mother’s lips and sometimes, I speak like her.

My tone gets low and weary when I worry,

Then loud and piercing when my daughters hurt me.

I try to hurt them like they might know better.

The years keep slipping away from me and I forget who I am.

My daughters shape themselves into the kind of women they would’ve liked me to be.

I can barely recognise myself.

When I look at them I see all that I was and then, all that I could have been.

They have my hands, my lips and my eyes

And they tell stories and love and laugh.

I try to hold on to the moments we have

But they suffocate under my grip.

So, I let them go and set them free

And I can only hope that they love me enough to remember me.

Then ensues that lonesome and longing wait,

For them to come and remind me a little of the love we used to keep.

I am my daughter.

I have my mother’s hands and my father’s smile.

I care about the world and I get caught up in the dreadful tide of change.

There’s this longingness for a future built on better grounds than what was given to me.

I believe there’s a bigger purpose in life and I chase it like I might lose sight of it all at once.

I’m scared to meet my mother’s eyes because they remind me of what life might do to you.

Oh, but I love her, I do, I love her till my bones ache

But I cannot love her enough to be her.

I claw at my flesh and I put on clothes that fit me weirdly.

And when I bring myself to look in the mirror, I can’t help but hate it all.

I have my mother’s hips; I have her thighs.

I have her belly and now, they are starting to have their lines.

I love my mother, I love her, I do!

But I can’t help depriving myself of nurture, of love, of food.

I can’t bear looking like her

Else my future might look like hers too.

I am my mother’s daughter.

I walk like her.

I put one foot in front of the other, with my head tilted to the side.

My limbs are taking me down the path that she knows all too well.

Part of her wants me to, but part of her is barring me,

Part of me is wanting her and part of me is fleeing.

I have an abundance of dreams – some great expectations – that I am so very determined to conquer.

And with my mother’s love heavy on my back, I trudge, I falter, I persist.

The years are only just slipping away; I and my future with them.

When I stand up and cross boundaries and dance,

The world cradles me in her arms and loves me so very gently.

Sometimes I feel that I might make it out of that abyss of longingness.

I cannot be my mother.

I cannot be my mother.

I cannot be my mother.

And yet I am, I have her eyes.

I have her lips, her hands, her belly and her thighs.

When I grow tired from the weight of the world,

I drink tea at the dining table - sweet, creamy and piping hot.

At 3 am, I am restless, cold and confused.

I carry my mother’s thoughts and worries,

I carry them because I have come to realise that they were always mine.

As time wedges itself between us,

My mother is slowly weakened by her maturity - the kind that only comes with age.

And as she leaves her youth behind,

She’s unaware that it’s being passed on.

And when I look in the mirror, I cry a little.

I am my mother.

I am my mother and not just my mother’s daughter.

I am my mother and I have her life.

I live as she might have and I love as she does.

And when I feel the tides of change rushing in and drowning me

I run back to her like a child, like a leech,

And I feed on the love she always keeps for me.

Reflection of Belonging

Jade Lent

St. Catherine University, Minnesota, USA

Poor Little One

Ken Donovan

Cottey College, Nevada, Missouri, USA

Poor little one with ears so gentle

hears a low banging drum with sounds influential.

Bearing steady rhythm,

but the tune does not appeal.

But the tune is the anthem,

so their feelings stay concealed.

Poor little one who doesn’t know what awaits.

They cannot see past the overwhelming gates.

In fact, unaware that it’s a gate after all,

but an enormous, inevitable wall.

Made with stone and forged with steel,

but in time will make circumstances ideal.

The poor little one couldn’t be more wrong

this is why I’ve written this story-like song.

Because when the wall becomes a gate

the gate shall open to reveal true fate.

As it begins to crack a light shines through

a light that is pure and true.

It whispers “Come closer, I am here to heal.

Your poor little mind they tried to steal.

Accept me for I accept you.

However you feel is what you shall do.”

The poor little one is sure it can’t be.

“I don’t deserve to be careless and free.”

But the poor little one couldn’t be more wrong

the suffering has past and they’ve been so strong.

As the gate begins to crack a light shines through.

The light a cure, their mind and heart grew.

The poor little one has gained the wealth,

the wisdom to care for their heath.

The wisdom to understand their worth

Know all who love them, everyone on earth

Three Poems

Katherine San Filippo

Salem College, North Carolina, USA

Wandering Towards

How carefully we walk this street,

tripping over cobblestones

making our way towards

buildings shining gold in the night

-our home awaits.

How often we make this journey,

trudging through the cold;

peeking through the sleet,

dim streetlights light our way

-our bones ache.

How do we look I wonder?

to those looking from above

(through fogged over windows)

our two bundled figures

-our unknown fate.

How sweet our relief is,

reaching home

striking matches to light our way,

frozen fingers untying scarves

-your joyous face.

Glimpses of My Mind

I wander along the tracks of

great ideas rusted over,

and sit and wait for the tangents

that never seem to come home.

I walk along the shallow bank

of an ephemeral thought

and without a care in the world

make a bridge out of pennies.

I sail the Mare Imbrium

and feel drops of clarity

that dry as another bright star

distracts me from the journey.

I travel the miles between

my brain and my tripping tongue

and wonder who could understand

my creaking trains and deep space.

Thoughts on Mortality

How do we move on

after death has died

(after all those we love are gone)?

We greet each dawn

like the world is on our side

-but how do we move on

(without being withdrawn,

without starting to backslide)

after all those we love are gone?

Are we more than a pawn?

More than some god’s joyride?

How do we move on

from these fears of the beyond?

Inevitably, we will sit dry eyed

after all those we love are gone,

and we will finally be alone.

There’s no guide

for how we move on.

After all, those we love are gone.

Two Poems

Time Perception

Joanna Zhang

Meredith College, North Carolina, USA

I am ten. I am wearing a grin and my grandfather, mother, father, sister, cousin, and aunt also have smiles, or the semblance of one in the case of my aunt. We are wearing long sleeves and pants, bright red blossoms of color against muted grays. My grandmother, grandfather, and I are sitting in the front. I am in the middle, with my other relatives standing in the back. Some of us noticeably have deadened expressions. My uncle seems to be unprepared for the camera, but I wonder at my grandmother’s face. For some reason, my grandmother looks winter-cold as she stares straight into the camera. Her lips are arranged as if she ate something sour that morning and is remembering the taste of it. Why does my grandmother look so acidic? Perhaps it is having to pose for a picture, or the press of bodies surrounding her, making her claustrophobic. Or, is it that she does not enjoy being with her family at all? Even studying this history in pixels, I do not know; I only know that I remember her more for her expression than if she had been smiling.

I am ten. I am wearing a grin and my grandfather, mother, father, sister, cousin, and aunt also have smiles, or the semblance of one in the case of my aunt. We are wearing long sleeves and pants, bright red blossoms of color against muted grays. My grandmother, grandfather, and I are sitting in the front. I am in the middle, with my other relatives standing in the back. Some of us noticeably have deadened expressions. My uncle seems to be unprepared for the camera, but I wonder at my grandmother’s face. For some reason, my grandmother looks winter-cold as she stares straight into the camera. Her lips are arranged as if she ate something sour that morning and is remembering the taste of it. Why does my grandmother look so acidic? Perhaps it is having to pose for a picture, or the press of bodies surrounding her, making her claustrophobic. Or, is it that she does not enjoy being with her family at all? Even studying this history in pixels, I do not know; I only know that I remember her more for her expression than if she had been smiling.

I am ten. I am wearing a grin and my grandfather, mother, father, sister, cousin, and aunt also have smiles, or the semblance of one in the case of my aunt. We are wearing long sleeves and pants, bright red blossoms of color against muted grays. My grandmother, grandfather, and I are sitting in the front. I am in the middle, with my other relatives standing in the back. Some of us noticeably have deadened expressions. My uncle seems to be unprepared for the camera, but I wonder at my grandmother’s face. For some reason, my grandmother looks winter-cold as she stares straight into the camera. Her lips are arranged as if she ate something sour that morning and is remembering the taste of it. Why does my grandmother look so acidic? Perhaps it is having to pose for a picture, or the press of bodies surrounding her, making her claustrophobic. Or, is it that she does not enjoy being with her family at all? Even studying this history in pixels, I do not know; I only know that I remember her more for her expression than if she had been smiling.

Reminiscent Flows

Medhavi Gupta

Indraprastha College for Women, New Delhi, India

I left early

The gathering that was making me swirly

I text a stranger I met

On the internet

As I sit in the metro and look at the happenings by

I see two youngsters stumble in

The train

Their hands touching

Triggering something akin to pain

The glimpse of their hands flitting around the steel

A sinking feeling in my chest, making me reel

As the crowd engulfs the lovelorn

I am lost in a sea of bygones

I step out of the station

The gloom and grey of the metro compliments my ruminations

I come to the present

When my imaginations are disrupted

As my line of sight is filled with blue

By the interruption of the ether

I come to

I greet the stranger

To whom I have no tether

He compliments my cheeks, my flesh prison

I nod and go on

I tell myself

Let bygones be bygones

Hectic pace of modern life

Thin, silky ice on the river

Ayumi Beeler

Smith College, Northampton, Massachusetts, USA

And I am just asking for something true and clear.

But meaning comes to me jagged, fractured and blue and cold.

I can’t make sense of this brightness.

Do I find myself on the lake bed?

Or am I in the ballroom, again?

Lit in rosy hues by the stained glass,

quaint little heels creaking the floorboards, stirring the dust –

Almost like: I want someone to come to me, this time.

I don’t want to have to go to them.

I am trying to dream of something other than hollow space,

but the dream itself is the gauze of this gown’s lace train,

thin as frost, glittering, almost disappearing

when I hold it to the light.

They have placed me alone here in the center of the dance floor, a crooked and wasting doll.

I am the painting’s centerpiece, is that it?

(And you are not here at all.)

Somewhere out on the lake a mallard dips below the silver of the water, and,

re-emerging, shakes the droplets from his head.

His lover swims a little ahead of him. Her feathers are plainer than his.

Yet they both shine.

Emotional Reflections of a Woman

Tutorial Level

Fern Schiffer

St. Catherine University, St Paul, Minnesota, USA

Attempt 1:

Roommate sits down across from you, and starts crocheting.

>Say hey.

While the words form in your brain and travel to your lungs for air, they get caught on something in

your throat. You lose.

Attempt 2:

Roommate sits down across from you, and starts crocheting.

>Take a deep breath, and hold it for a while.

>Look up from your laptop and say hey.

Roommate looks up, and back down. You lose.

Attempt 3:

Roommate sits down across from you, and starts crocheting.

>Take a deep breath, and hold it until that thing in your throat releases

>Look up from your laptop and say hey.

>Say how’s the homework been today?

Roommate shrugs and says okay, there’s too much of it but that’s how it is.

>Shrug back.

>Say that’s rough.

Roommate looks up, then back down. You lose.

Attempt 4:

Roommate sits down across from you, and starts crocheting.

>Take a deep breath until that thing in your throat unclenches its teeth and slinks back into its cave.

>Look up from your laptop and say hey

>Say my god, oh my god, am I doing this right

Attempt 5:

Roommate sits down across from you, and starts crocheting.

>get up and walk to your bedroom

>close the door behind you and wait for the world outside to stop rendering

Attempt 6:

Roommate sits down across from you, and starts crocheting.

>think to yourself about how you can’t even talk to your friends

>think to yourself about your roommate just sitting there.

>think to yourself that these are only words! How hard are words! Just talk!

>Look up, then back down

Attempt 7:

Roommate sits down in a chair in the living room, you haven’t left your room all day.

Attempt 8:

>try to say that’s a beautiful thing you’re making

>all you can do is stare

Attempt 9:

Roommate walks into the living room to grab a skein of yarn, and then returns to a bedroom which

will never render

Attempt 10:

>say that’s a beautiful thing you’re making.

>say I wish I could do that.

>say I’ve tried to make beautiful things before but there was always someone else I’d rather watch

Roommate looks up.

Six Month Lease

Cheyenne Main

Cottey College, Nevada, Missouri, USA

It’s a shoebox of a room;

A shut window, a home fit for a fly

A poor woman’s tomb

Shipwrecked in an interstice of time

Its bony frame trembles, stretched in skin

Oak wood doors and linoleum floors

Desiccated, a man’s hair thinned

No tangible history, or veiled folklore.

A closet stands in the corner

Arms crossed, hooks hanging down

Peering with scorn at the foreigner

Who measures his narrow stance with a frown.

But this place is mine, if only for a while

A new home, a comfortable exile